Back

Hiking hits new heights in Sea to Sky

Whistler is perfectly poised to make the most of the overwhelming interest to adventure outdoors

Alison Taylor

Just as the first signs of summer began to sprout, the air heavy with the smell of the earth reawakening and the promise of another season, Bryce Leigh was exploring in the forest close to Rubble Creek, an area between Squamish and Whistler. Leigh, the president of the Whistler section of the Alpine Club of Canada (ACC), has been hiking in the Sea to Sky area, and beyond, since 1971. There are places in the local backcountry, like Rubble Creek, that are as familiar to him as the contours of his face. Yet, on this particular spring day two years ago, Leigh saw something he had never seen before—a group of people appeared before him in search of the trailhead to picture-perfect Garibaldi Lake … in flip-flops and tank tops. The lake was roughly 9km away with 900m of elevation gain. To top it off, there was probably half a metre of snow on the ground at the alpine.

Leigh relayed all of this information to the group, who he estimated were in their thirties. They were, however, not to be deterred, and carried on in search of the trailhead. Keep in mind, this was May 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic had forced the world into seclusion for the previous three months; everyone wanted to feel the sunshine, to breathe deeply in fresh, clean air, to get some respite from the overwhelming burdens of everyday life at that time.

In Whistler, it’s really easy to be inspired; it’s really easy to be humbled as well,” says Leigh. “It’s great that people are getting out. But they’re not prepared at all.

In recent years, backcountry exploration has skyrocketed in Whistler and everywhere else in B.C. Hiking in particular has boomed as people look for ways to get into nature. And while there are ongoing challenges with this growth, it has also paved the way to welcome new guests and to provide more opportunities to show off the tremendous beauty of the Sea to Sky corridor. Whistler is primed to make the most of this boon.

West Side Story — Sproatt, Rainbow, Skywalk

Though no one could have foreseen the pandemic that would change the world, several years ago the Resort Municipality of Whistler could see the writing on the wall when it came to the mounting pressure on the backcountry.

Its solution: The Alpine Trail Network. This network would span the west side of the valley on Mount Sproatt and Rainbow Mountain, an alternative to the options on the east side of the valley, primarily in Garibaldi Provincial Park. There were existing trails in the area; the Alpine Trail Network would take them to the next level with a $1.1 million investment over several years.

It’s a remarkable area,” says Mitch Sulkers, who helped build portions of the new trail. “It’s quite dense in terms of scenic values.

The roughly 58 kms of trails are designed as non-motorized and multi-use,with some specifically designated as hiking-only.

We are extremely committed to these trails and think they are critical tourism assets for Whistler and for Canada.

Whistler Mayor Jack Crompton

The numbers are telling. In 2018, the municipality recorded 5,550 hikers in the area. That jumped to 7,980 the following year and to 9,700 in 2020. Last summer was an anomaly; the season was cut short and the trails were closed due to grizzly bear activity. Still, 6,000 hikers were counted.

By controlling and funding the trails, however, the municipality can also manage the experience in the sensitive alpine ecosystem, and in particular, can continue to protect a valuable municipal asset: the 21 Mile Creek Watershed, a critical part of Whistler’s water resources. Part of that commitment includes providing park rangers that work seven days a week throughout the summer, educating hikers and bikers and keeping a watchful eye over the area.

The municipality is extremely proactive. They’ve jumped in with both boots on.

Whistler Search and Rescue manager (WSAR) Brad Sills

East Side Story — Spearhead Huts, Garibaldi Provincial Park

Meanwhile, on the other side of the valley, there has been a similar story of investment and improvement. Jayson Faulkner, who has championed the Spearhead Huts proposal from the outset, says this summer is shaping up to be a busy one at the Kees and Claire Hut at Russet Lake. It is the first to be built of the three backcountry huts planned on the Spearhead Traverse in Garibaldi Provincial Park, giving hikers and climbers access to a world-class high alpine route—and yet one more way to fuel the growing demand for unique, and legendary, backcountry experiences.

“There’s a huge amount of demand that’s not going away for people to get outside,” says Faulkner, who can see that demand first hand in the 2022 summer bookings with projections that the hut will be at 100 per cent capacity over summer weekends.

Sadie Brubaker hiked the area last summer, uploading via the gondola and then the Peak Chair on Whistler Mountain and then hiking along the area known as “the musical bumps.” Rather than stay at the hut, which was often closed last year due to COVID requirements, Brubaker camped in a spot close to Russet Lake, surrounded by the natural beauty of the alpine water and the majestic mountains. The hut also added to the experience in its own way.

It looks like a castle on the hill above the lake.

Sadie Brubaker

While Brubaker is hesitant to describe herself as a seasoned hiker, she loves the feeling of accomplishment that comes at the end of a long hike and, “doing something hard and feeling good about it.”

Hiking became a respite of sorts during the pandemic, especially in the early months, as she looked for things to do outside. “It became a daily project to find somewhere to go that I hadn’t been,” she says.

Once you get out there, it’s easy to get hooked.

In many ways, Whistler offers something for every hiker—from the uninitiated who want to take a walk in the forest to the experienced multi-day traveller looking to get away from it all.

Pressure mounts

Hiking’s growing popularity, however, is not without its challenges.

Where once the vast majority of calls to Whistler Search and Rescue were in the winter (85 per cent), that number has shifted to 50/50 in the last five years.

“Hiking is chief amongst the increase,” says Sills.

Many are not prepared for the challenges that lie ahead. Often groups have done little research or planning: they set off without enough water, they don’t anticipate weather with poor clothing choices in an environment that can change rapidly, and there is often a complete reliance on cell phones that may not have service. These are just some of the rookie mistakes.

“The hikes around here tend to be missions,” explains Sills.

Another factor to consider is that many new hikers are objective driven.

They are, for example, determined to get to the turquoise waters of Garibaldi Lake to take a photo and post it to social media, or take a picture at Iceberg Lake on the SkyWalk Trail, typically accessed above the Alpine subdivision.

Sulkers was a key trailbuilder on SkyWalk. At its upper portion, there aren’t a lot of trail markings and it’s not a wide path. It’s easy to lose the trail.

And while Iceberg Lake draws you in with its beauty, the bergs are the remains of avalanches—hard, frozen, old snow that’s easy to slip on.

“At times people seem to push the learning curve,” adds Sulkers.

The pressure isn’t just mounting on calls to search and rescue; the infrastructure in certain areas is also struggling to keep up with demand.

Take Semafore Lakes, says Sulkers: “It’s just been hammered in the last couple of years in particular.”

There are no washrooms there, no garbage collection. And people aren’t always practicing “pack it in, pack it out.”

“That’s a big challenge for us,” says Leigh, as groups like the ACC look for ways to educate new hikers.

The flip side, of course, is that the more people discover the backcountry and its delicate ecosystem and its beauty, the more people are then converted to protecting it and cherishing it.

“If people experience it, it’ll help them to preserve it,” says Leigh.

The Future

All indications point to a busy summer on the local trails.

“(Walking or hiking) is one of the very best things we can do for our health,” says Faulkner. “This is an important thing for society. We are hardwired to be in nature.”

Whistler, he adds, is primed to make the most of that demand.

“The focus continues to be delivering well-managed, world-class alpine experiences,” adds Crompton.

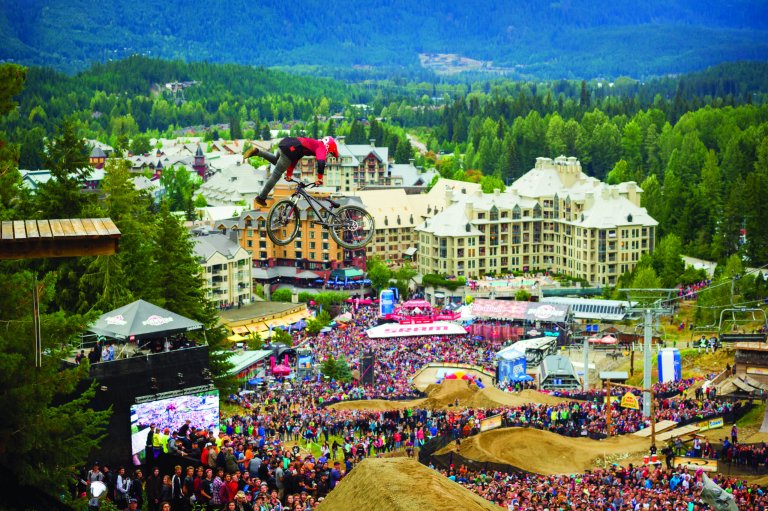

This is a place of exceptional and extraordinary nature: big animals such as grizzlies and black bears, imposing fauna and forests, vast wilderness. Not to mention, there’s a world-class resort sitting on the doorstep to all this natural grandeur.

Faulkner adds: “It’s very clear that outdoor experiences are on the top of everyone’s list.” And there’s no better place than Whistler to get outside.

By: Whistler Magazine

GuidedBy is a community builder and part of the Glacier Media news network. This article originally appeared on a Glacier Media publication.

Location

Topics

Recommended Spotlights

Related Stories

-

Hobbies & Leisure Whistler

Trail Mix - Things To Do & See [In & Around Whistler]

It’s a testament to Whistler, and the people who have long called this place home, that the town dreamt up as the ultimate...

-

Art Galleries Whistler

Global events inspire artistic evolution

War and the pandemic have an impact on local artBy Alison TaylorThere is something about the painting Just Stop that catches...

-

Hobbies & Leisure Whistler

Trail Mix - Things To Do & See [In & Around Whistler]

It’s a testament to Whistler, and the people who have long called this place home, that the town dreamt up as the ultimate...

-

Art Galleries Pemberton

Whistler’s architectural evolution

Highlighting the award-winning built environment By Steven Threndyle It all seems like ancient history now, but Whistler’s...

-

Local Attractions Whistler

Top Summer Activities in Whistler

The snow is melting, the birds are chirping, and the flowers are starting to bloom. Sumemr has finally arrived in Whistler! If...

-

Food & Drink Abbotsford

4 Dishes to Make with Summer Peaches

Summer is the perfect time of year to experiment with different ways to use peaches. These juicy, refreshing fruits can be...

-

Home & Garden Abbotsford

How to Create a Zero-waste Household

Reducing your household waste can help the planet in many ways. You may even be able to eliminate your waste completely if...

-

Beauty & Wellness Abbotsford

7 beauty trends for summer 2021

You may be looking forward to re-entering society this summer or at least looking better during a video meeting. Beauty trends...

-

Gifts Abbotsford

Four fabulous experience gift ideas for mom this Mother’s Day

If you’re tired of giving the same old types of Mother’s Day gifts, treat your mom with an experience instead. There are many...

-

Home Furniture & Decor Abbotsford

Working from home? 4 tips for your home office setup

Working from home can be a better experience for you with the right office setup. Setting up your in-home office correctly can...

-

Whistler

Long-term State of Mind

There’s an age-old debate in Whistler about what, exactly, constitutes a “local.” Does it refer to the number of years spent...

-

Antiques, Furniture & Decor Whistler

Art in the Time of Covid

When the COVID-19 pandemic first hit, Mountain Galleries wasn’t sure what to expect. Would anyone come out to buy art? Would...

-

Local Attractions Whistler

Backcountry Bounty

Whistler is bracing for a busy season beyond the ski area boundaries. The backcountry is beckoning like never before as skiers...

-

Food & Drinks Whistler

Classic Comforts

Many of us have found comfort during these strange times with a glass of wine. Whether you venture out to one of our...

-

Canadian Whistler

Comfort Food for Uncomfortable Times

In a year in which our lives have been completely upended, it’s often the simple things that manage to bring the most...

-

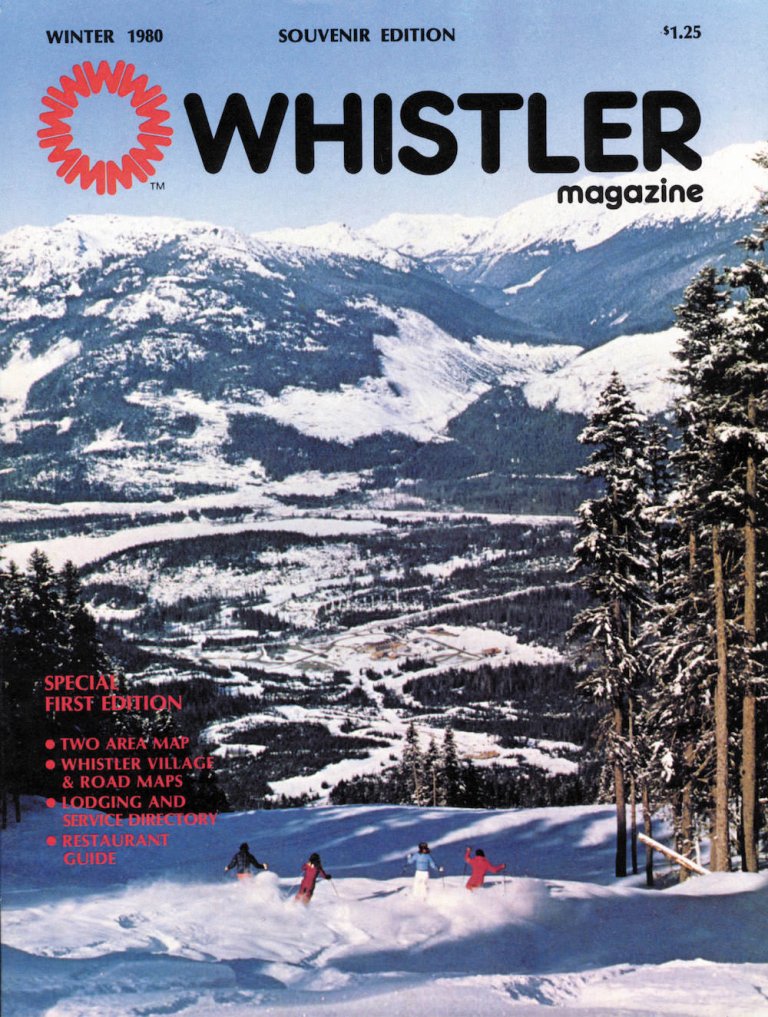

Photography Whistler

Four Decades of Telling Whistler’s Stories

For a Whistler photographer, few things beat landing the coveted front cover of a ski magazine. Greg Griffith knows. SKI,...

-

Casual Dining Whistler

Safe and Cozy

Even Whistler’s finest restaurants offer a more casual vibe; such is the nature of ski resort dining where guests are often...

-

Design & Renovations Whistler

True To Its Past

The romantic and rounded form of the traditional log cabin, once a staple in Whistler’s architectural landscape, has seen its...